Evolution of Tray Landscapes in Early 19th Century Japan Based Upon the

Senkeiban, Senkeiban Zushiki and the

Tokaido Gojusan-eki Edyu, Hachiyama.

Three illustrated early 19th century books document the transition from Chinese to Japanese influences in viewing stone appreciation.

By Thomas S. Elias

The early 19th century was an important period in the transition from Chinese to Japanese influences in viewing stone appreciation. Three illustrated books of tray landscapes published in that period document that transition.

The

Senkeiban (1808)(占景盤), its later edition

Senkeiban Zushiki

(1826)(占景盤圖式), and the

Tokaido Gojusan-eki Edyu, Hachiyama

(53 Stations of the

Tokaido) (1848) (東海道五十三驛鉢山図繪), were produced and printed in Osaka which was the center for Chinese culture and the tray landscape movement in Japan in the early 19th century. By the late 1840s, the rapidly rising popularity and influence of Japanese culture expressed in

ukiyo-e

woodblock prints served as a stimulus for the development of fifty-three tray landscapes based upon the 53 Stations of the Tokaido, one of the ancient travel routes from Edo (Tokyo) to Kyoto.

Creating miniature landscapes in bowls ranging from shallow to deep, and rectangular containers originated in China and later spread to Japan. These three-dimensional decorative pieces connect the appreciation of viewing stones with the art forms of penjing and bonsai.

Tray landscape arrangements can be traced to the Tang dynasty (618-902 CE) where tomb murals showed people carrying trays displaying single or multiple rocks. Rock penjing, one of the two major divisions of Chinese penjing, is a landscape arrangement where natural rocks rather than miniature trees serve as the medium of expression. The practice of developing rock landscape penjing continued from that time to the present. I believe that the Chinese rock penjing influenced the later development of tray landscape scenes in Japan and those, in turn, influenced the 20th century Saikei, a form of tray landscape introduced by Kawamoto Toshio.

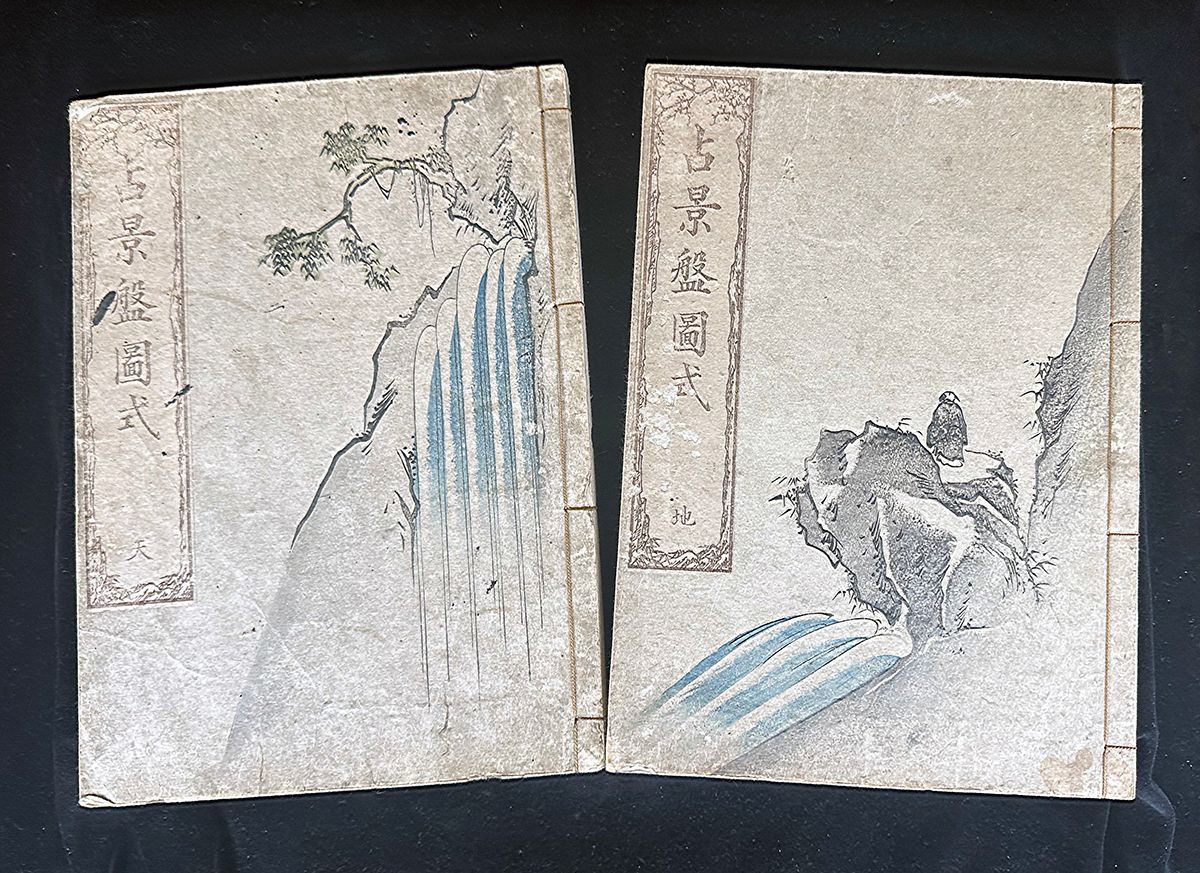

Senkeiban (1808) and Senkeiban Zushiki (1826),

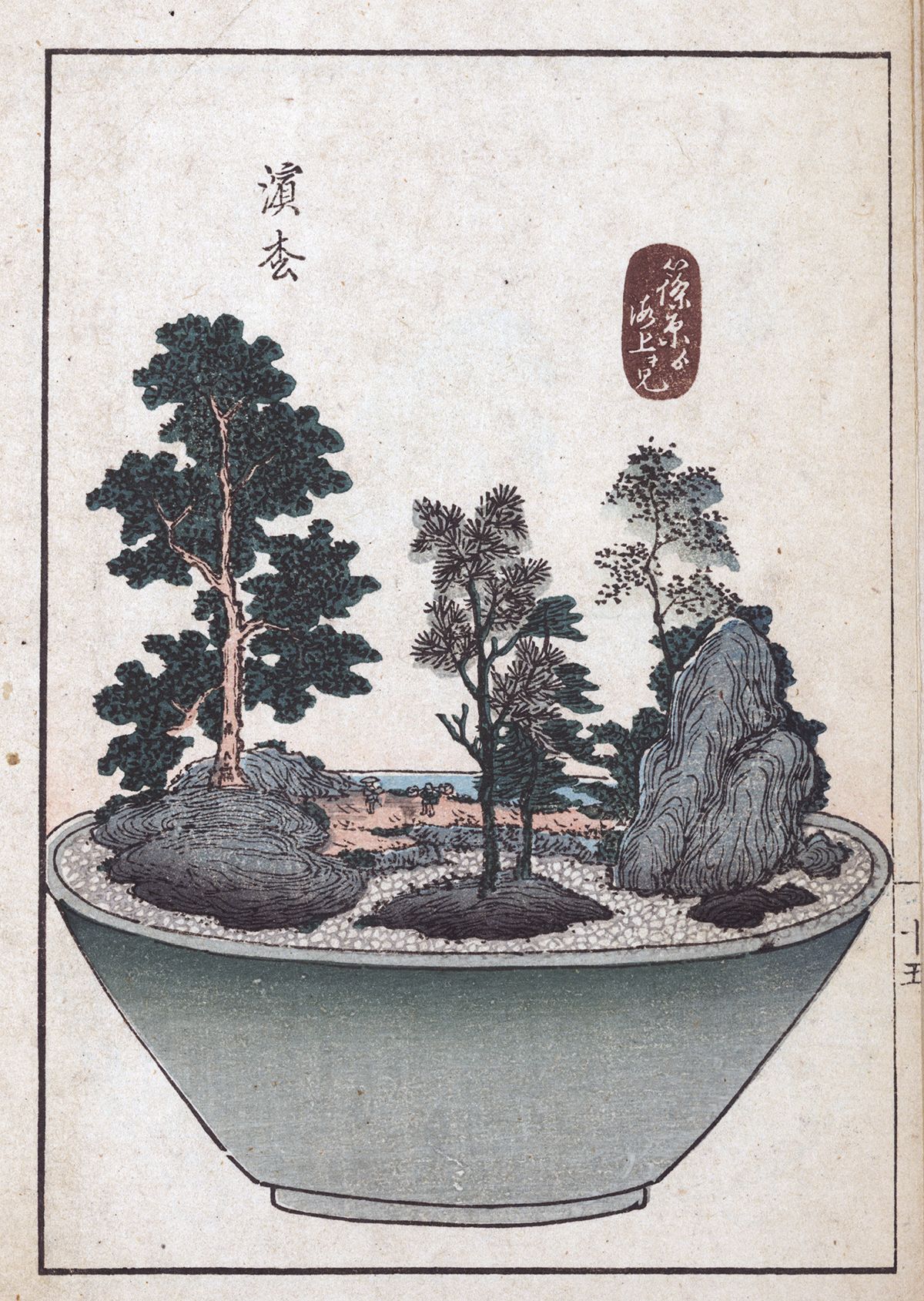

According to Kawami (2018), Sumie Buzan was a sword maker who later in his life painted Chinese-style tray landscapes. After his death, his son, Sumie Aizan, published twenty-four of his father’s paintings in the single volume Senkeiban in 1808. Sumie Aizan published a two-volume edition in 1826, Senkeiban Zushiki (占景盤圖式) Illustrated Styles of Tray Landscapes containing the original twenty-four paintings plus an additional thirteen paintings by his father. These paintings are of imagined scenes rather than miniature reproductions of actual places. Sumie Aizan included two pages of illustrations of tiny accompanying objects (boats, pagodas, houses, bridges, and temples) used in adding detail and scale to each landscape tray. Information on how to make the tray landscape was included in the last few pages of his book.

The word Senkeiban is a Japanese word that can be interpreted as landscape tray and was used historically in Japan for landscape scenes inspired by Chinese tray landscapes.

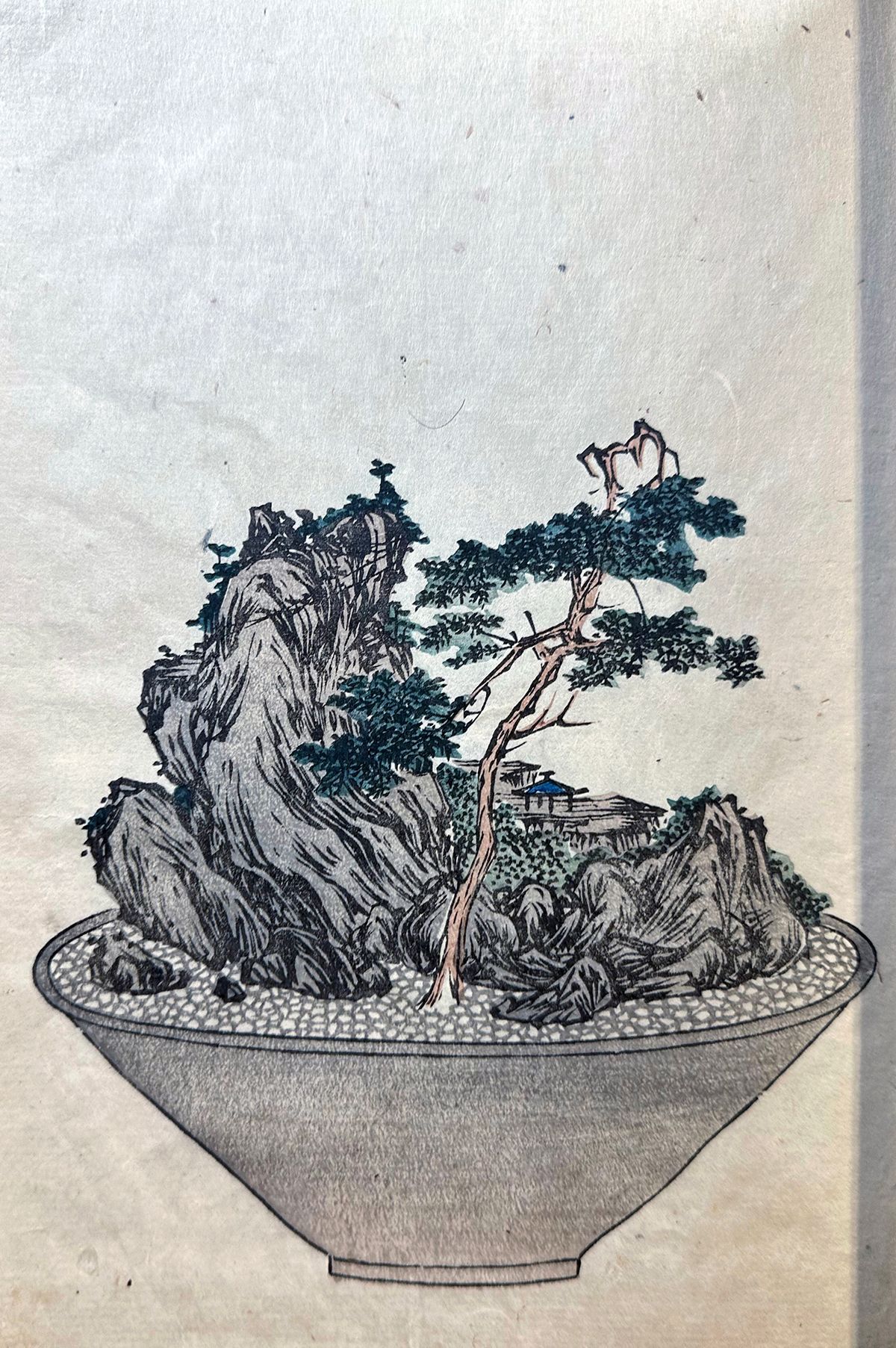

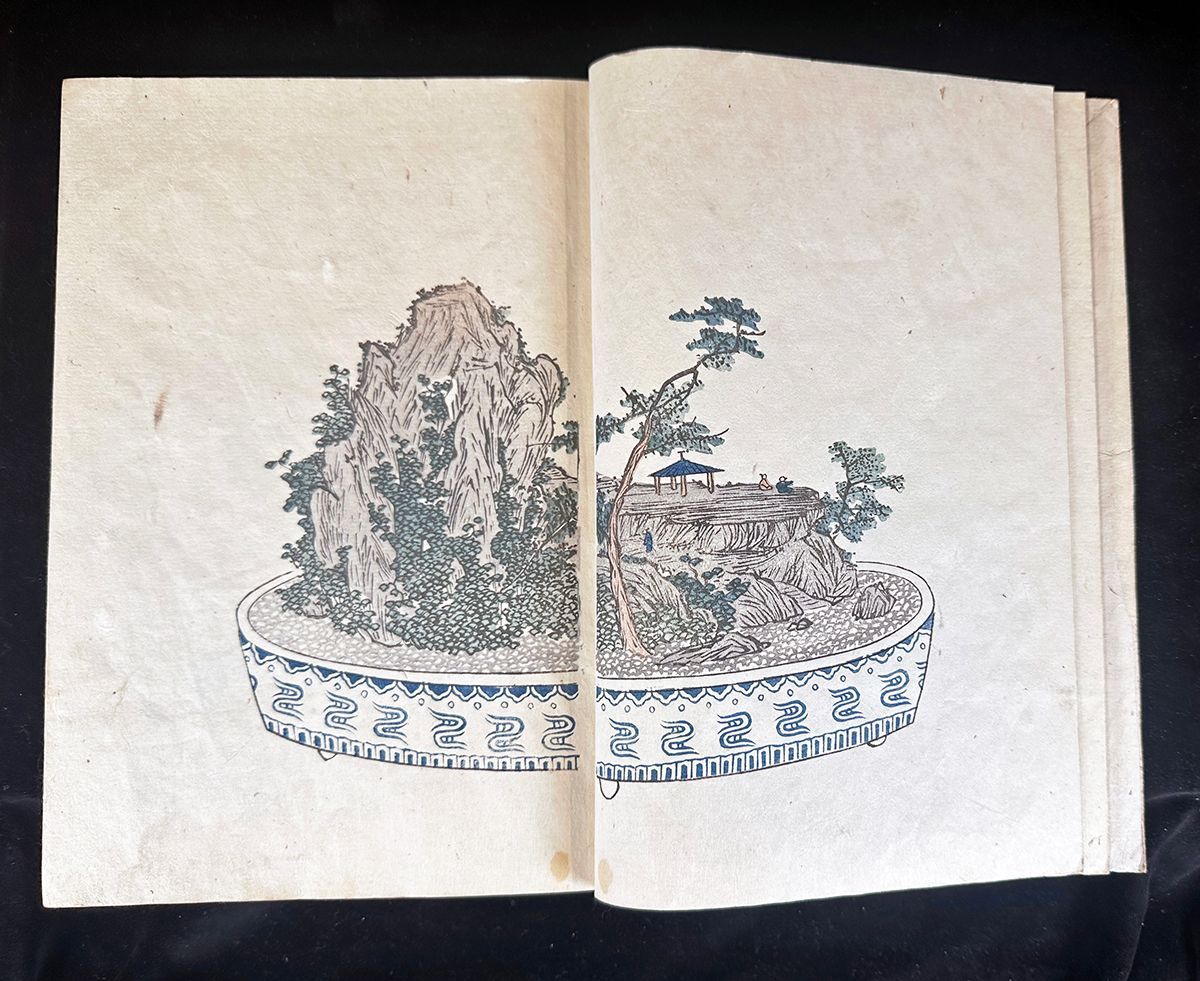

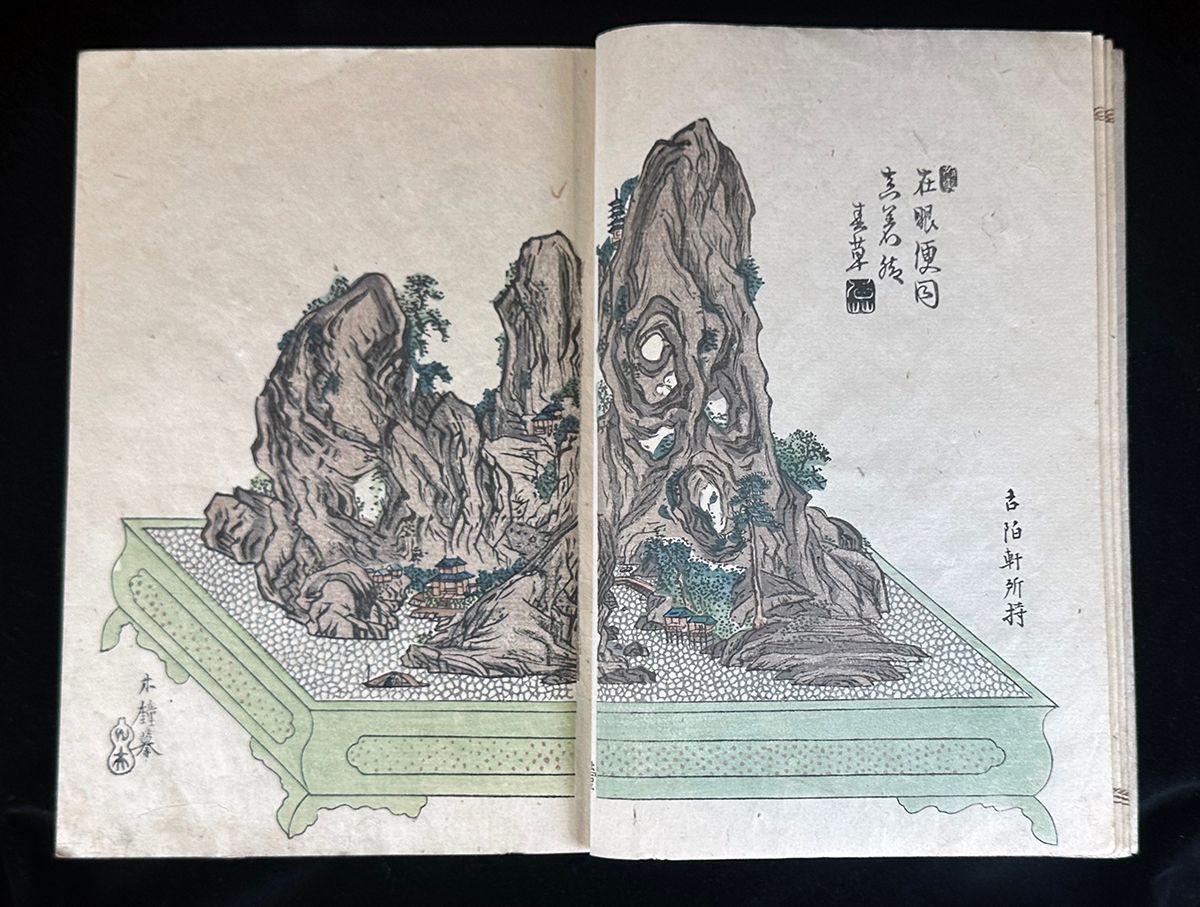

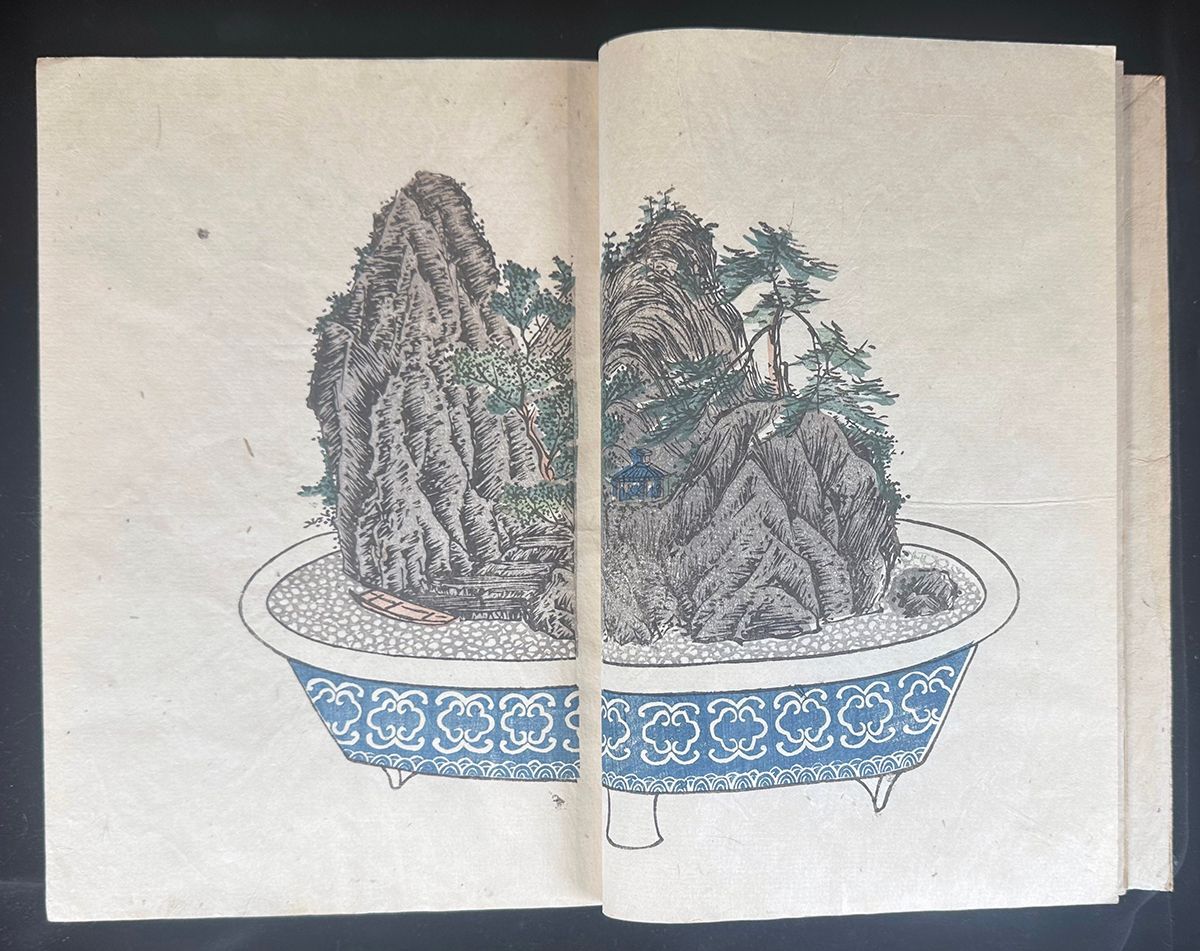

Two of the twenty-two full page illustrations in Senkeiban Zushiki showing the decorative motif on some pots, and the plain unadorned style on other pots.

Tokaido Gojusan-eki Edyu, Hachiyama (1848)

This two-volume book is similar in size and format to Seikeiban Zushiki, and contains illustrations of fifty-three woodblock prints that were based upon a similar number of actual tray landscapes that depicted the fifty-three stations of the Tokaido. Two additional paintings representing the beginning and ending points were included in this book. Each painting can be identified with one of the way stations along this historically important route. The actual tray landscapes were made by Kimura Tosen, a resident of Osaka. Tosen was regarded as an intellectual who loved Chinese culture including stones. It is highly probable that Tosen was aware of and may have known Sumie Aizan and the Senkeiban Zushiki as part of the intellectual community appreciating Chinese art and culture in Osaka. This coincided with the rise and popularity of the Japanese style woodblock prints and the popular woodblock series Tokaido made by Utagawa Hiroshige. Hiroshige’s fifty-five print series of the stations of the Tokaido was published between 1833 and 1834, and became the best-selling Ukiyo-e in Japan at this time. This well-known travel route became even more famous after the publication of this print series.

Tokaido Gojusan-eki Edyu Hachiyama (1848) title page

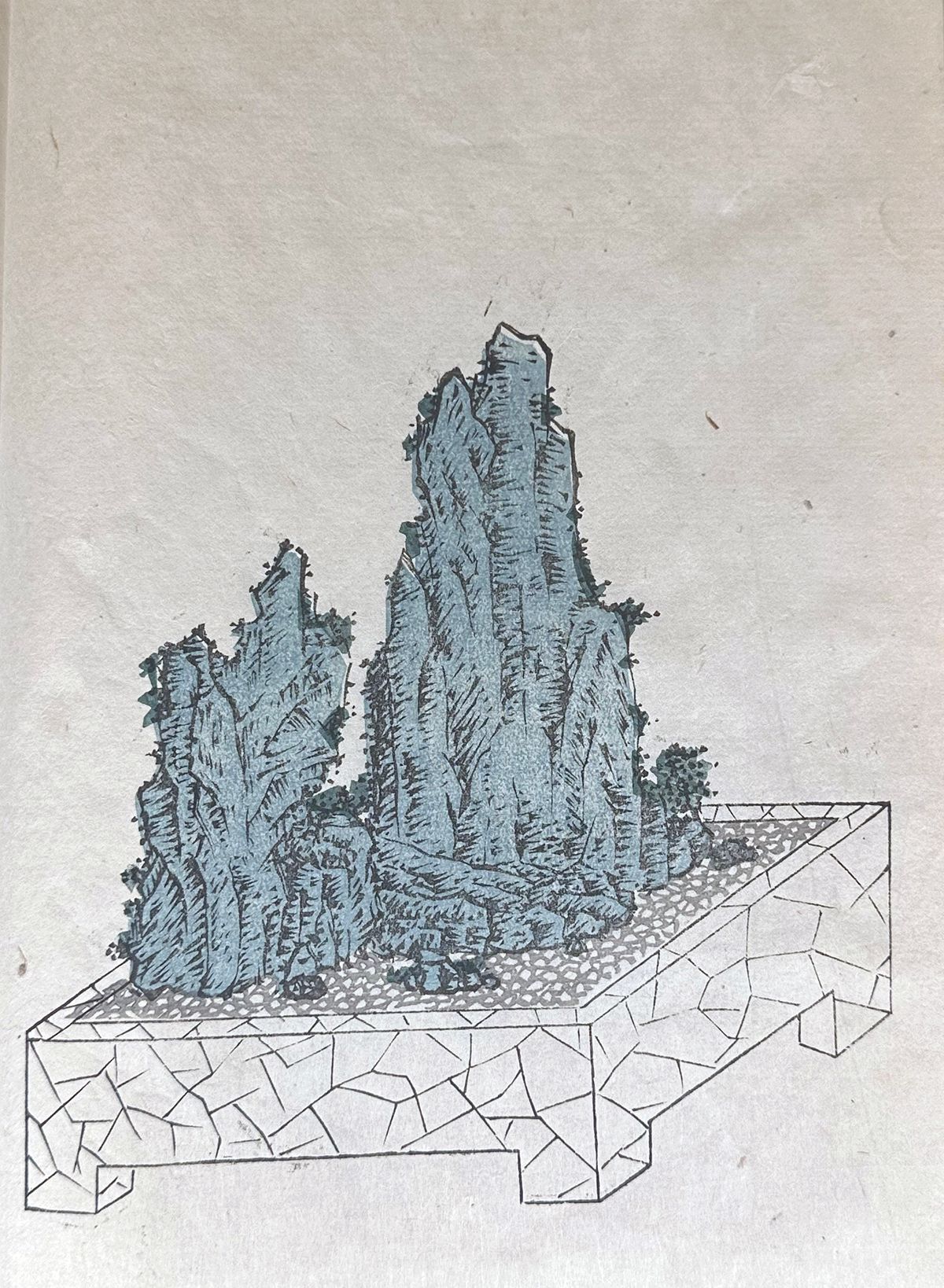

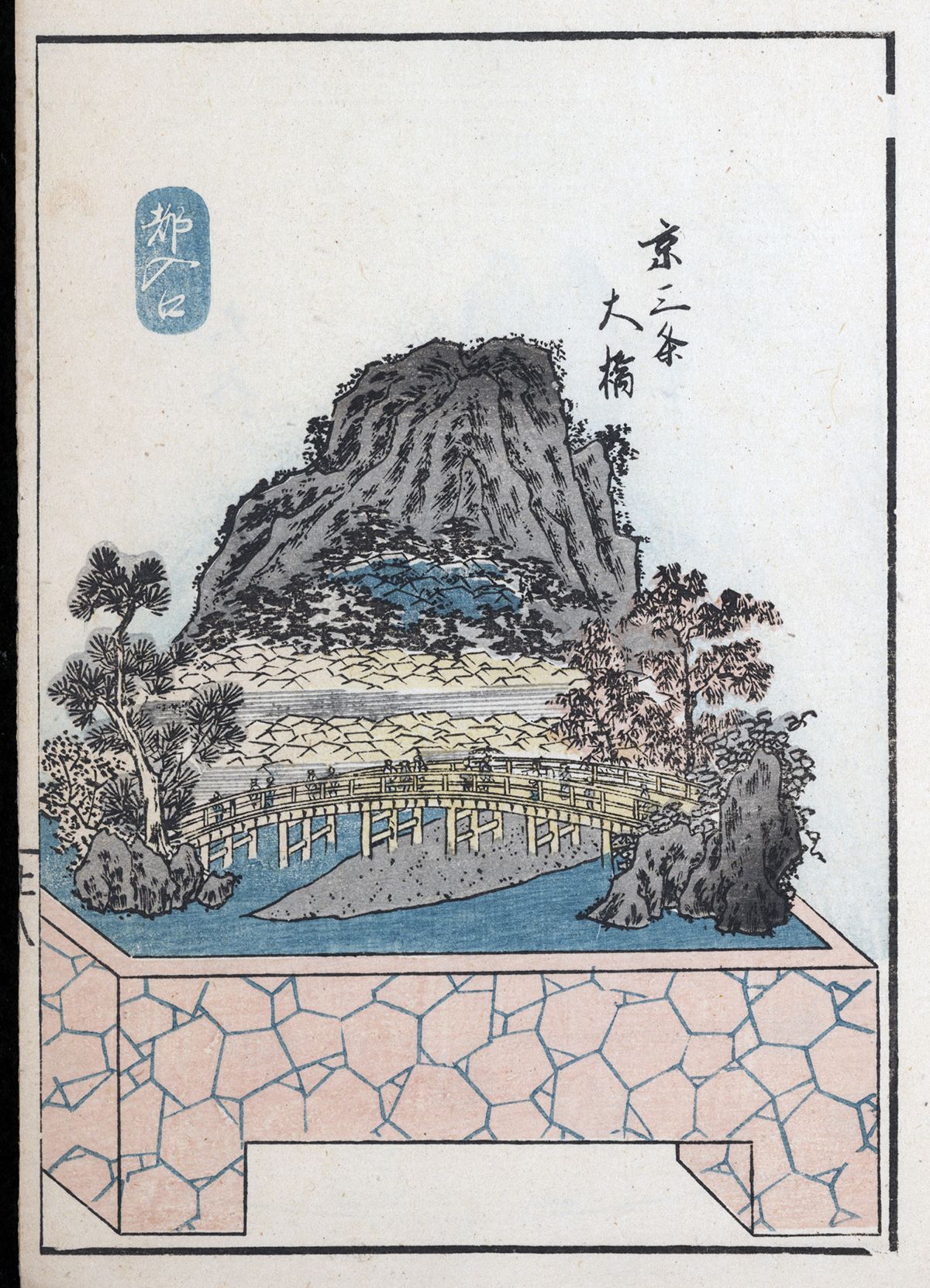

Kimura Tosen engaged Utagawa Yoshishige, a lesser-known Ukiyo-e painter in Osaka, to make fifty-three paintings of Tosen’s tray landscapes. Since these were distinctive Japanese tray landscapes, they were labelled as Hachiyama (鉢山) to distinguish them from Senkeiban. The transition from using the word Senkeiban to Hachiyama in the books’ titles is noteworthy. The main distinction between the two works is that the former is based upon imagined landscape scenes and in the latter, Utagawa Yoshishige’s paintings were based upon actual places in Japan along the Eastern Sea Route connecting Edo and Kyoto. Tosen’s Hachiyama and Yoshishige's paintings utilize more small accessories including miniature bridges, houses, pagodas, and other structures than in the earlier Senkeiban books. Tosen’s and Yoshishige's works are more detailed and intricate than Sumie’s earlier books, and greater emphasis was placed on the features and materials used to construct the Tokaido stations. Arai Yui (2019) pointed out that in the 1848 Hachiyama volume, the stones painted as mountains were similar to the features and colors of stones that occur near each of the corresponding stations.

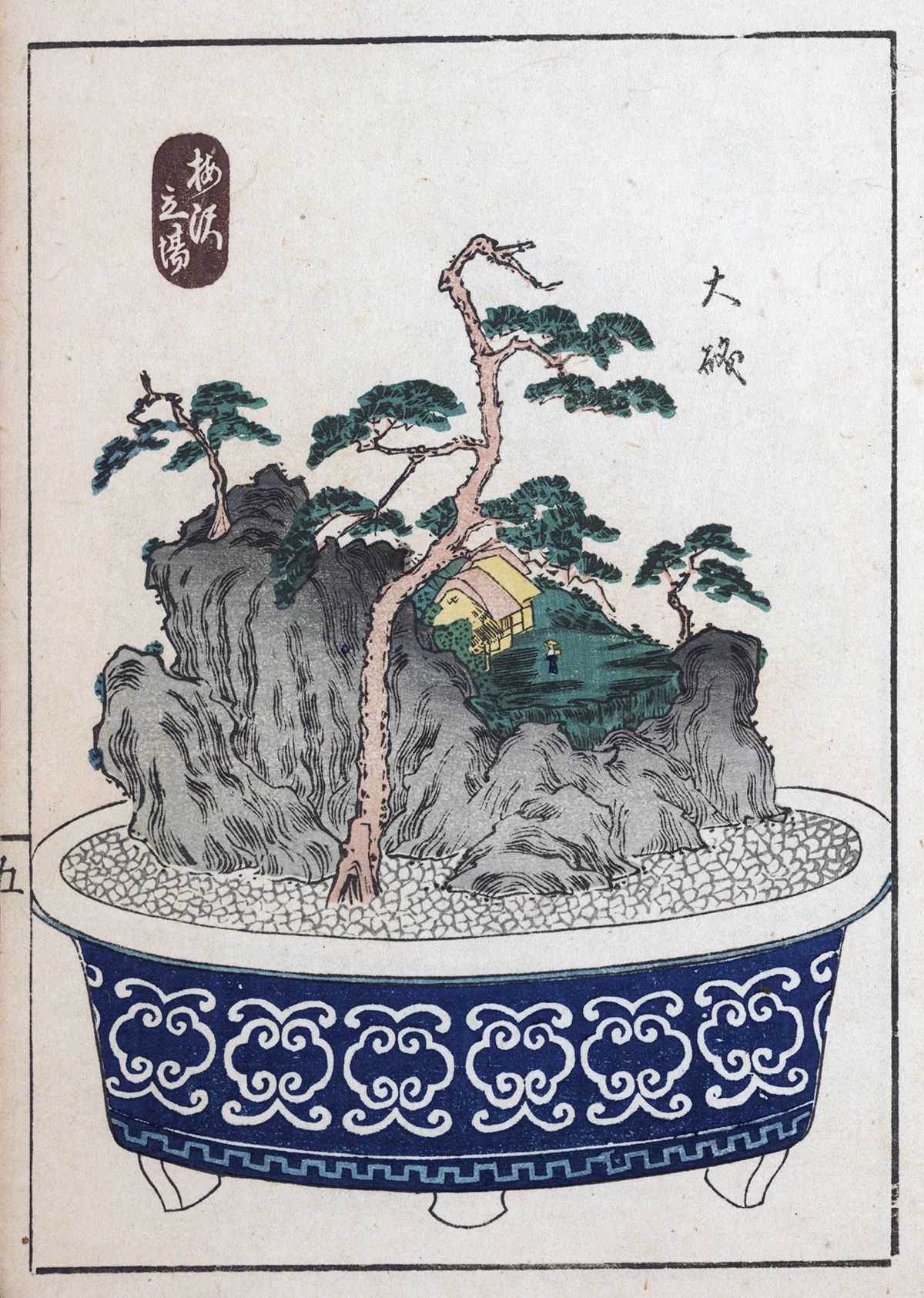

These two illustrations of different stations of the Tokaido Gojusan-eki Edyu, Hachiyama (1848) illustrate the greater use of small accessories, painted mountains, and more site-specific details.

Comparison and Conclusions

The Tokaido is considered as a combined product of the influences of Utagawa Hiroshige’s Tokaido woodblock print and the earlier Senkeiban Zushiki. While there are considerable differences in the design and construction of the landscapes, there is a similarity between the pots illustrated in both books. Nine of the pots illustrated in Tosen’s 1848 Hachiyama book are identical to pots illustrated in Sumie’s 1826 Senkeiban book.

As a result of this study, I concluded that:

- Tray landscapes creating different landscape scenes using unusual rocks, small plants, and accessories in ceramic trays were popular in the 19th

century in the Edo period in Japan. This practice was initially influenced by Chinese rock penjing until it developed into its own distinct Japanese form of tray landscape by mid-19th

century. The

Senkeiban Zushiki was influenced by Chinese style landscape trays.

- The

Senkeiban Zushiki

is one of the earliest Japanese Illustrated books featuring unusual stones used in pots (tray landscapes) as aesthetic objects. The scenes depicted are imagined, not a stylized reproduction of a known site.

- The 1826

Senkeiban Zushiki

served as a reference that Kimura Tosen and Utagawa Yoshishige used, at least in part, for the production of his 1848

Tokaido Gojusan-eki Edyu, Hachiyama. Sumie Aizan was a contemporary of Kimura Tosen in Osaka where both books were compiled and printed.

- The 1846

Tokaido Gojusan-eki Edyu, Hachiyama

shares some similarities with the earlier volume, but illustrates the growing impact of the Japanese wood block prints on changing tray landscapes to a greater identity with Japanese art and culture. The use of the word “Hachiyama” in the title of the 1848 book is an indication of this transition.

- The Tokaido Gojusan-eki Edyu, Hachiyama combined the appeal of Ukiyo-e in early to mid-19th century with the popular hobby of tray landscapes to promote stone appreciation practices in Japan.

____________

References

Arai

Yui. 2019. 唐船作、歌川芳重画『東海道五十三駅鉢山図絵』研究

ー上方の広重需要と唐物趣味ー新井 ゆい.

The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road as Potted Plants by Kimura Tōsen and Utagawa Yoshishige: The Demand for Hiroshige and Chinese Wares in the 1 Region. Bulletin of Kitajima Institute of World Art. (Nihon Kunsei Bijyutu Kenkyu. 2: 1-22. 2019.

Elias, Thomas S. (2019, May 1). Chinese Rock Landscape Trays (Rock Penjing). VSANA. https://www.vsana.org/newpage976040a7

Kawami Norishisa. 2018. 墨江武禅の刀装具制作ー江戸時代における絵画と工芸の関係性ー川見 典久. The Japanese Sword Fittings SUMINOE Buzen Carved as Painter: The Impact of Painting on Craftwork in the Edo Period. Bulletin of Kitajima Institute of World Art. (Nihon Kunsei Bijyutu Kenkyu. 1: 4-20. 2018.

Note: The source material used in this study was an electronic copy of the 1808

Senkeiban

in the National Institute of Japanese Literature, Tachikawa City, Japan; an original of the 1826

Senkeiban Zushiki is in the VSANA Library. The 1848

Tokaido Gojusan-eki, Hachiyama

is located in the Special Collections of the USDA National Agricultural Library.