Cultivating Viewing Stone Appreciation: Bonsai Winnipeg’s Evolution

The 2023 exhibition staged by the Bonsai Society of Winnipeg, Canada included an exhibit of 48 viewing stones, many as contemporary displays. The challenges encountered in the exhibition are discussed.

By Joe Grande November, 2023; Photos by Scott Samson, courtesy Bonsai Winnipeg

The Bonsai Society of Winnipeg, situated at the geographical heart of North America, represents a quintessentially Canadian bonsai community with a membership of 110 individuals, predominantly devoted to the art of bonsai cultivation. The society’s demographic alignment with similar North American counterparts underscores the broader trends within the bonsai subculture on the continent.

However, this unity in their love for bonsai starkly contrasts the relatively underdeveloped appreciation of suiseki or viewing stones, which historically shares its origins in the same aesthetic circles as bonsai. Winnipeg’s climatic constraints, characterized by a condensed growing season of five months, compel its members to seek alternative pursuits during the protracted winter period. Some engage in crafting bonsai tables and ceramic pots, while others undertake the challenging task of nurturing tropical bonsai indoors under grow lights. A smaller yet dedicated faction of the society gravitates toward the intricacies of viewing stones, carving their own wooden bases for these unique stones.

The obstacles encountered by the nascent viewing stone community within Bonsai Winnipeg are multifold. The initial hurdle is procuring suitable stones from local and regional sources. The arduous task of crafting wooden bases, conforming to the minimalist Japanese or elaborate Chinese styles, is an insurmountable challenge. The need for more resources, such as bronze dobans and ceramic suibans, further hampers the progress of viewing stone enthusiasts.

What became apparent was that interest in stones was commonplace among our members. Some brought back beautiful stones from their summer cottages, which they found on lakeshores, creeks, and hiking trails. Others brought back stone souvenirs from vacations in other parts of Canada. Apart from the memories associated with these stones, many had the potential to be thoughtfully exhibited as viewing stones.

However, the community’s need for more geological education compounded our struggles. An understanding of geological processes, mineral classification, and the unique geological heritage of the Manitoba region was conspicuously absent. This lack of geological literacy deprives the enthusiasts of the ability to discern what constitutes a commendable viewing stone.

To mitigate these challenges, several strategic interventions were employed. The dissemination of geological knowledge was initiated through presentations delivered during general meetings by Joe Grande, a dedicated geology enthusiast within the society. These lectures encompassed a classification of stones and minerals into the three primary categories: igneous, metamorphic, and sedimentary, and furnished illustrative instances of local stones from each category. Furthermore, these presentations offered a comprehensive overview of Manitoba’s geological terrain, spanning from the gold-bearing granite outcrops of the Precambrian Shield in the northeast to extensive sedimentary deposits exceeding 200 meters in the south.

The educational efforts were further supplemented by Paul Collard, an ardent collector of viewing stones. Collard regaled the members with personal narratives of his collecting expeditions, beguiling them with anecdotes of the magical moments and locations that yielded his treasured specimens. His collection comprised stones acquired during vacations, cross-country journeys across Canada, gifts from friends, and purchases from international stone vendors.

Joe Grande’s earlier presentation, examples from the book Contemporary Viewing Stone Display by Richard Turner, Thomas S. Elias, and Paul A. Harris, served as a catalyst for renewed enthusiasm. This innovative approach to viewing stones invigorated the collective imagination of Bonsai Winnipeg’s viewing stone enthusiasts.

These collective endeavors bore fruit in the form of a substantial display of 48 viewing stones exhibited by six members during the 2022 Annual Bonsai Display. Initially drawn by the allure of bonsai, visitors were captivated by the viewing stone on exhibit. This success kindled a fresh determination among the stone enthusiasts to elevate their exhibition the following year.

Earlier that year, a field trip was organized for stone enthusiasts to explore the Agate Pits in Souris, Manitoba. These pits, a repository of agates, jasper, sandstones, petrified wood, dendrite stones, basalt, diorites, and porphyry, proved a veritable treasure trove. The site, created by glacial deposition, yielded an abundance of unique minerals and rocks, igniting the participants’ fervor for viewing stone appreciation.

After this monumental acquisition, the challenge of presentation and appreciation was addressed through a specialized workshop. Stone collectors were invited to present their acquisitions and receive guidance on effective display methods. Joe Grande elucidated the diverse categories of viewing stones, encompassing landscape, object, figure, pattern, and abstract stones. His demonstrations extended to the meticulous cleaning of stones and applying artisanal patinas, notably camellia oil. In parallel, Paul Collard shared his proven techniques for carving wooden bases, expounding on the complexities of this art form.

Interestingly, the workshop revealed that while carving wooden bases remained a formidable challenge for most, there was burgeoning interest in unconventional approaches to stone presentation. This shift in perspective bore testament to the transformative power of education and exposure.

Another hurdle in viewing stone’s progression lies in the apprehension surrounding the secure exhibition of these valuable specimens. Some viewing stones are compact enough to be easily concealed, prompting concerns about theft during exhibitions. Hiring a security firm to monitor the exhibit encouraged many members with small trees and stones to participate.

This evolving mindset precipitated a new dawn for Bonsai Winnipeg’s viewing stone enthusiasts. Inspired by the VSANA Contemporary Viewing Stone Gallery, they rallied to present a remarkable collection of 51 stones, contributed by 12 exhibitors during the 2023 Annual Bonsai Display. Drawing inspiration from the innovative approaches witnessed in the Contemporary Viewing Stone Gallery, these individuals had found their artistic muse and charted a distinctive course within the viewing stone domain.

In conclusion, Bonsai Winnipeg’s journey from the limitations of a truncated growing season to a thriving community of viewing stone enthusiasts is a testament to the transformative potential of education, exposure, and innovation. By intertwining geological literacy, personal narratives, and contemporary inspirations, they succeeded in fostering a vibrant appreciation for viewing stones, thereby enriching the tapestry of their horticultural society.

Examples of contemporary viewing stone displays:

Paul Collard, The Polar Bear

Basalt

Vancouver Island

This stone was found along the ocean shore. The

daiza

(base) is maple burl.

Arlene Downey, Dragon’s Head

Petrified Mammoth Tooth

Unknown

Woolly Mammoths roamed the earth 300,000 years ago until approximately 1650 CE, grazing on shrubs and grasses on the cold tundras of Europe, Asia, and North America. In North America they roamed on the ice-free areas of Yukon, British Columbia,

Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Southern Ontario.

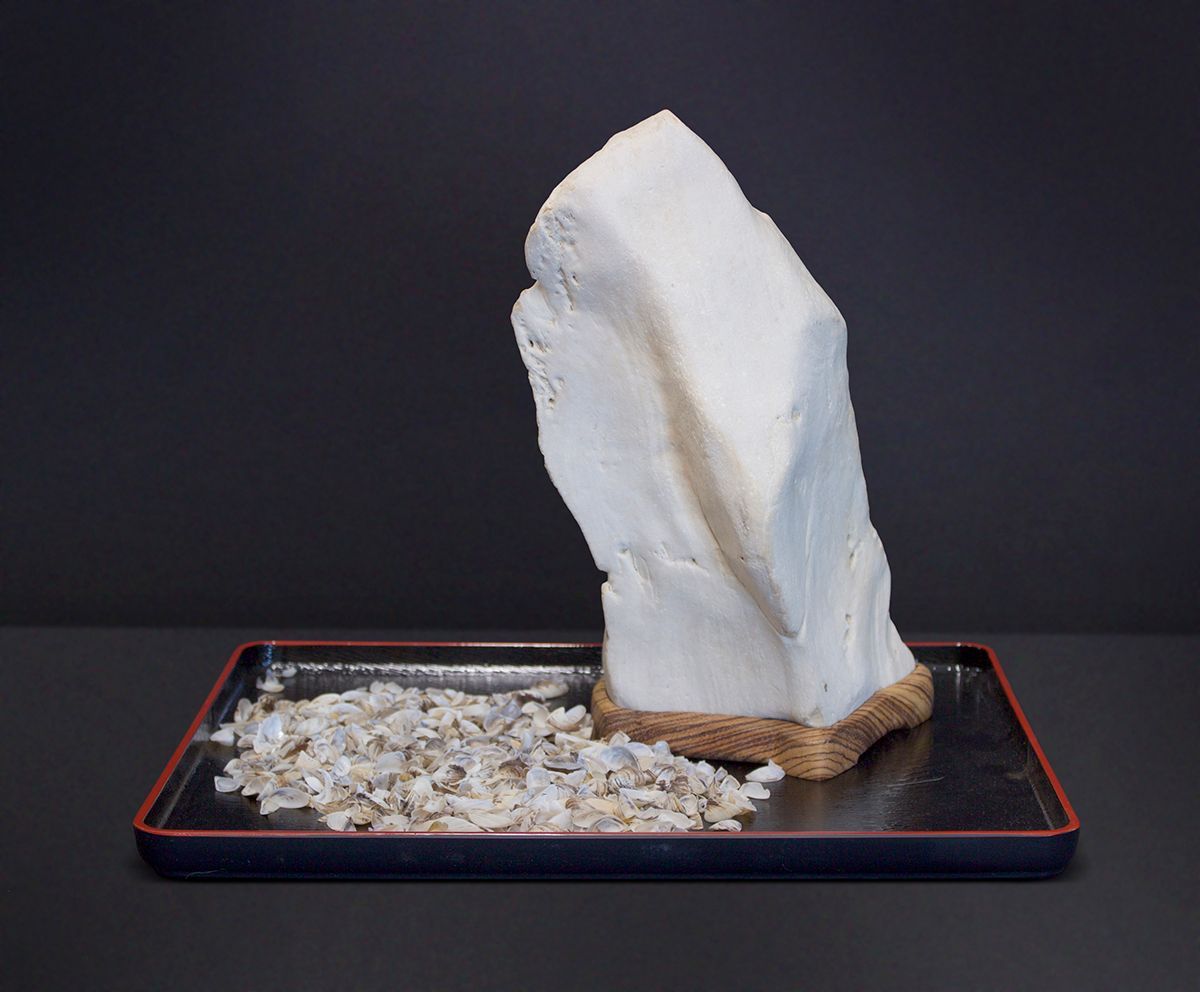

Joe Grande, White Visitation

Dolomite limestone

Chalet Beach, Lake Winnipeg

This captivating figure stone evokes the presence of a friendly ghost, reminiscent of the iconic white sheets children playfully don during costumed events. it’s accompanied with delicate shells, symbolizing the diverse marine life integral to the formation of

sedimentary stones. The base is meticulously carved from zebra wood, coated with a lustrous layer of camellia oil, adding contrast to its wave-like grain.

Paul Collard, Desert Moon

Jasper

Souris, Manitoba

Presented on an elm burl slab

Kathy Gutheil, Chrysanthemum Stone (in round pedestal pot)

Unknown

Unknown

Given as a gift about 15 years ago

Scott Samson, Grassy Peak

White Quartz with Lichen

British Columbia

Collected at the peak of a mountain in the interior of BC. The lichen is what originally attracted me to the stone, and I was afraid that the altitude change and a long journey in a suitcase would kill it. Six years later however, the lichen is flourishing and the illusion of a mountain in the hills is intact. Container was made by Steven Ahing.

Scott Samson, Mars-Mallow

Limestone

Lake Winnipeg

The presentation here gives the appearance of a giant toasted marshmallow on the Martian surface. One can only imagine what the NASA scientists might think as their Rover rolls past.

Matthew Majkut, AquaExtreem

Unknown

Collected south of Hecla Island, Manitoba.

When this stone was collected on a Lake Winnipeg beach, it looked black and was covered in clay. “She cleans-up real nice.”

Denis Girardin, Creat-ture

Basalt and granite

West Hawk lake area, Manitoba

Beware, explorers, of this macabre viewing stone. It sits on a red granite slab, presenting an eerie tableau of eroding basalt, where the mind may conjure images of decomposing skulls or ruptured heads.

This disturbing scene is set on an island of crushed black granite, encircled by a lush, alluring growth of moss. The allure is tantalizing, but be warned of the ominous danger that lingers when drawn to explore this island.

Arlene Downey, Skyward

Petrified wood

Souris Agate Pits

Sourced from the Agate pits of Souris Manitoba.

Joe Grande, Ursine

Hornblende Schist with Quartzite intrusions

Sandilands-Agassiz Interlobate Moraine, Manitoba.

The form of this stone evokes the shape of a black bear. This stone came from a decommissioned gravel pit near Ste. Geneviève, Manitoba. The base is natural driftwood from Chalet Beach, Lake Winnipeg. Does it look like a bear-like creature foraging on a beach? The white stripes remind some viewers of a skunk!

Kimberly Shillington, Untitled

Basalt stone with Quartzite and Granite intrusions

Canadian Shield, Northwestern Ontario

Contemporary display on a black tray with silica sand from a beach on Lake Winnipeg. The stone is wrapped between 2 deer antlers.