Scholars’ Rocks, Itineraries of Chinese Art

A Major exhibition of Chinese Stones in Paris, France

By Thomas S. Elias, June, 2012

Madame Catherine Delacour, curator-in-chief of the Chinese Department at the Musẻe Guimet, assembled 100 objects used by the literati and officials. These objects include natural stones; man-made, stone-like sculpture; furniture; containers; mounted slabs; seals; a screen; and various accessories. They have been integrated into one of the finest exhibitions featuring Chinese stones ever staged in the Western world. What makes this exhibition so successful is the way Delacour has organized and displayed excellent stones together with various art forms influenced by stones. After viewing this exhibit, even novice stone enthusiasts can better understand the relationship between stones and art in ancient China. The majority of the objects are on loan from Chinese scholar Zeng Xiaojun, while others have been borrowed from collections in China and the United States.

As you enter the museum, you are greeted by a large, columnar, Song dynasty garden stone inscribed by Qian Shisheng. This stone, measuring nearly 2.5 meters (7.5 feet) in height, makes a greater impression in person than merely looking at its photograph in the catalog. There are so many wonderful objects on display that it was difficult to decide which ones we liked best. We were quickly drawn to exquisite paintings of stones—some on scrolls. The life-like detail made them appear vibrant and warm. Viewing a Ming dynasty painting of a stone almost 500 years old was a moving experience. Several Ying stones were positioned so they could be seen from all sides. We wanted to pull up a chair and just sit and visually embrace the stone, but the presence of the museum’s security staff encouraged the more acceptable behavior of standing.

A highlight of the exhibit was a large Lingbi stone over a meter high and 1.8 meters wide on a very elaborate base, displayed in the center of the hallway. On the wall close to this stone was an incredible portrait of this very stone. The captivating painting by Lu Dan in 1953 was almost twice the size of the actual stone.

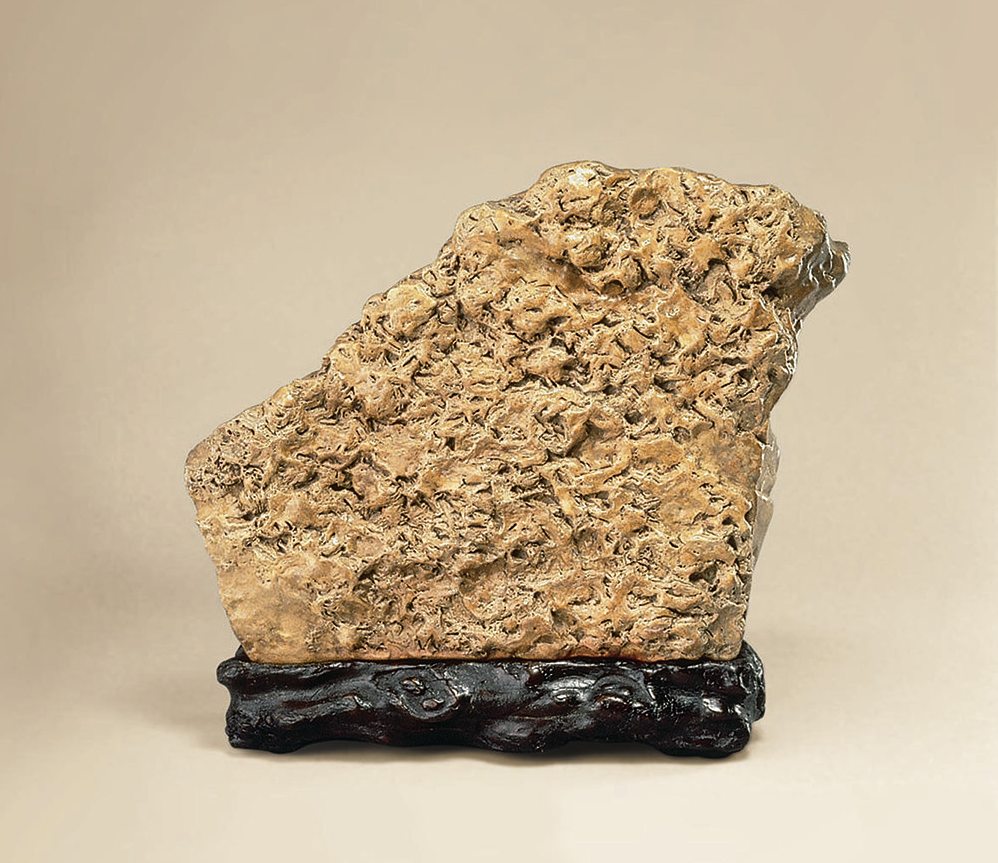

While there were many Lingbi and Ying stones displayed, a large and impressive Yellow Wax stone caught my eye. It is basically a slab with a rough surface resembling frozen fat on one surface and a smooth surface on the back side. This stone has a richer, deeper golden yellow color, more so than shown in the catalog. In China, we have seen many thin, smooth Lingbi-type stones that were used as musical instruments; this is the first time we have seen a natural thin shaped Lingbi hung on a stand for use as a chime stone. This Ming dynasty gem and its stand was one of my favorite pieces. Several of the Ming dynasty stones had been inscribed by their former owners, a feature that sometimes aids in dating the stone and determining its provenance.

Fossilized wood, roots, and even dried fungi were represented in the exhibition along with man-made, stone-like sculptures. Other artifacts include several Ming and Qing dynasty carved figures or bronze cast figures. Several pieces of Ming dynasty furniture, some large and very elaborate, captured the attention of virtually every visitor. It was easy to sit and image a Ming scholar entering the room, sitting at a table, contemplating one of the stones, and then lifting a brush to composed poem.

We liked the exhibit so much that we returned to view it again three days after the first visit. I regret that this exhibit will end after a short three-months and not travel to other museums in Europe, and in North America. One or more North American venues for this exhibit would help many people better understand Chinese stone appreciation.

The Musẻe Guimet, a major museum devoted to Asian arts, is located at 6, place d’lẻna in Paris adjacent to the lẻna Metro station. Hours are 10:00 to 5:00 p.m. every day. The museum charges a fee for admission to the museum and also a fee for this special exhibition. However, if you prefer, you can purchase tickets solely for this exhibit.